An Experiment in Paper by the Makers of Chocolate

On 17 October, 1960, the News Chronicle, a liberal daily that opposed fascism and stood for peace and reconciliation in international affairs, was sold to and absorbed by the Daily Mail, a newspaper that in 1934 came out in support of Oswald Moseley and the Blackshirts.

The death of the Chronicle at the hands of a rival almost entirely out of keeping with its policies and traditions has since been held up as an exemplar of everything that is wrong with the press in modern Britain. For socialist critics of 'press freedom', it reflected the constraints that advertising placed on editorial liberty; for liberal champions of it, the malign influence of 'restrictive practices' and trade unions; and for those who turned up at Bouverie Street on 17 October to find themselves unemployed, a lack of leadership among the board of directors.

So why did the Chronicle have to 'wither on the bough precisely at the moment when the nation was ripe to appreciate its liberal qualities’? - in the words of one of its star journalists. And to which of the loaded explanations for its death should a newspaper historian assign the most weight? In order to answer these questions, I contacted Sir Dominic Cadbury, whose father, Laurence, had been responsible for selling the newspaper over fifty years ago. In all the clamour and post-mortems that have surrounded the sale of the Chronicle, I figured, the one voice that seems to have been completely drowned out is that of the owners - the chocolate entrepreneurs, the Cadburys.

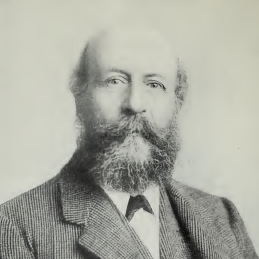

George Cadbury

The involvement of the Cadburys in the newspaper dates back to December 1900, when Lloyd George wrote to Sir Dominic's grandfather George, imploring him to rescue the then Daily News from business interests that backed the Boer War. The News, established 54 years earlier as an instrument for social reform by Charles Dickens, was the only national newspaper at the time to oppose the conflict in South Africa. George Cadbury obliged Lloyd George and invested in the newspaper, taking sole ownership as other benefactors reneged on pledges of financial assistance. The purveyors of chocolate had become purveyors of news.

“To endeavour by the circulation of newspapers ... to bring the ethical teaching of Jesus Christ to bear upon National and International questions.”

It was in this pre-history of the Chronicle that Sir Dominic saw the roots of its demise 60 years later. He read out to me a document drawn up by his grandfather in the office of his manor house in Oxfordshire, where I had been kindly invited for discussion. I listened intently, armed with a mug of tea and accompanied by Nelson, Sir Dominic's three-legged labrador. 'I am leaving in my will to the sons whose signatures are below shares in the Daily News Limited as a sacred trust', the document read. 'The objects for which the trust is established are: a) To endeavour by the circulation of newspapers ... to bring the ethical teaching of Jesus Christ to bear upon National and International questions, for example, to substitute the spirit of the Beatitudes for the military spirit, and the teaching conveyed in the parable of the Good Samaritan for so called Imperialism.' At this point, Sir Dominic looked up at me: 'well, can you imagine in today's world trying to run a newspaper on that premise?'

The problems that this Biblical mission must have posed to the running of the newspaper is beyond doubt, but I wanted to know how it fed into the demise of the Chronicle in 1960. As a former chairman of The Economist, Sir Dominic has a strong grasp of the mechanics of the publishing industry. He acknowledged the significance of all the explanations that had been put forward to diagnose the death of Chronicle: those relating to advertising, labour relations and management.

In so far as the editorial position of the Chronicle was based on what was ethical rather than popular, Sir Dominic did not believe it could survive in an industry in which advertising was king. When it took a stand against the military intervention of Britain in Suez, for example, it lost 100,000 readers overnight, suffering a blow to its advertising revenue from which it never recovered. The newspaper was therefore penalised for refusing to succumb to the base jingoism on which the Daily Mail prospered. To wage for peace had no marketing logic; to wage for war clearly did.

Edward Martell's New Daily on 'The Murder' of the Chronicle.

Where critics of press freedom have highlighted the role of advertising in the death of the Chronicle, champions of it have highlighted that of labour relations and trade unions. Edward Martell, editor of the non-unionised New Daily and founder of the Freedom Group, claimed at the time that the Chronicle was over-staffed by a proportion of one-third as a result of restrictive practices. It could have been run - and would have possibly survived - on a staff of two rather than three thousand. In Martell's view, Laurence Cadbury's position as a left-wing proprietor made him particularly vulnerable to the demands of the printing unions: his historic association with workers' rights prevented him from taking them to task. Sir Dominic, though shocked at the number of workers the Chronicle employed, was sceptical of this argument. As has been shown in a separate blog, pay and restrictive practices were tied to industry-wide agreements that were manipulated by the more powerful proprietors. 'They knew that the restrictive practices were costing the Chronicle more in a relative sense than their own papers', remarked Sir Dominic: 'I'm sure they would have said that the Chronicle won't survive and the Cadbury family will never stay the course'.

While advertising revenue and labour relations are factors that all newspaper businesses have to negotiate, these can be managed and overcome with effective leadership and long-term planning. The Cadburys, it was alleged, were simply never equipped or committed enough to save the newspaper. Laurence Cadbury came into particular criticism for not sharing the ideals that the newspaper and its staff embodied. As Sir Dominic admitted, between his grandfather and father, the Chronicle went from being one man's passion to a family's burden: Laurence and his brothers simply did not share their father's burning radicalism or religiosity. The Chronicle drained family money and its Biblical mission made it almost impossible for George's successors to turn it into a profitable enterprise: 'you can't imagine a Rebecca Brooks signing up', Sir Dominic quipped.

It is difficult not to study the Chronicle, at times a magnificent newspaper that died with a daily readership of over one million, without being swayed by sentiment. After meeting with Sir Dominic, however, I struggled to see how it could have survived. My only remaining question was 'why the Daily Mail?' Surely it deserved a better place of rest? If the Cadburys were to operate as a business rather than a charity, then in truth they had no other choice. Had the sale of the Chronicle been advertised, the advantage gained by buying its readership would have been lost: the whole of Fleet Street would have been able to compete for its readers.

The experiment in paper by the makers of chocolate, then, sadly had to come to an end and public life was much the poorer for it. Just as the Cadburys had for a period of 60 years paid a high price to translate their ideals into print, the public also paid one when the Chronicle finally passed to an opponent far less worthy.